THE EVOLUTION AND PLASTICITY OF GEOTHERMAL THREE-SPINED STICKLEBACKS

Under climate change we can expect global mean surface temperatures to increase by several degrees within the next hundred years. Fish, as ectotherms, are expected to be particularly vulnerable to climate-change driven increases in surface temperatures. Wild fish populations will need to either migrate to cooler temperatures or adapt to persist, while fisheries and aquaculture will need to adjust and adapt as well. Gaining an understanding how how fish populations are affected by, and can adapt to thermal habitats may prove invaluable in climate change response efforts.

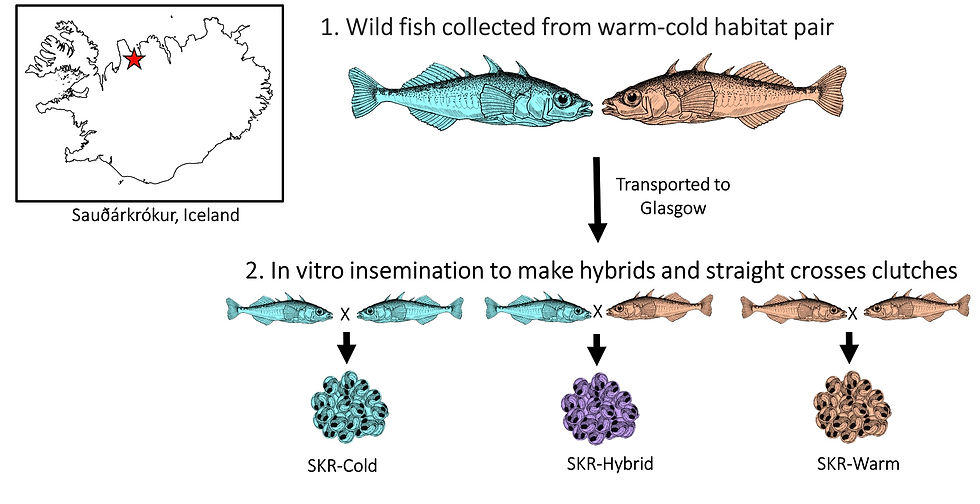

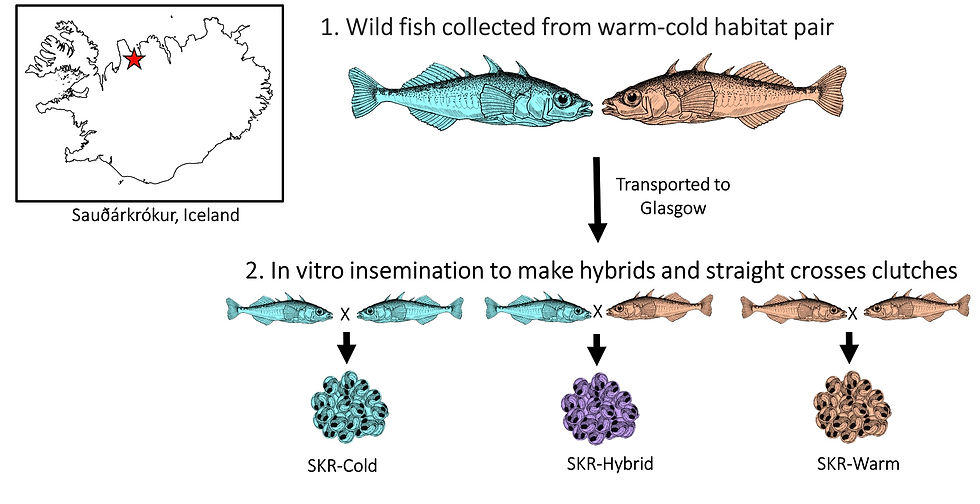

My PhD project aims to address this by taking advantage of a natural warming experiment - Geothermal activity in Iceland results in naturally heated water flowing into cold water bodies. This creates wide temperature gradients over very short spatial distances, meaning that warm and cold habitat pairs are otherwise very similar. Several of these habitat pairs are inhabited by Three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus), a species of fish particularly well suited to ecology and evolution research. These fish have been found to be diverging in several traits, such as body shape, so it is possible that they have already adapted to their native thermal habitats.

Using complementary field-based reciprocal transplant and lab-based multi-generational experiments I aim to answer the following questions;

-

Is this divergent morphology adaptive?

-

How do warm and cold sticklebacks differ in gene expression?

-

How does their gene expression respond to transplantation to the alternate habitat?

-

What are the heritable and trans-generationally plastic components of divergent gene expression?

-

How is hybrid gene expression affected by thermal habitat?

For this experiment sticklebacks were collected from warm-cold habitat pairs and brought to the lab in Glasgow. Here they were bred via in-vitro insemination to produce egg clutches. In addition to straight-crosses, hybrid-crosses were also made

After egg clutches were produced they were split evenly and randomly in half, with half of the eggs going to 12oC and the other half to 18oC. The eggs hatched and the fry reared to sexual maturity, at which point liver and brain tissue was collected for gene expression analysis

A field based reciprocal transplant experiment complements lab-based experiments by capturing more aspects of the thermal habitat.

For this experiment sticklebacks were collected from warm-cold habitat pairs and brought to the lab in Glasgow. Here they were bred via in-vitro insemination to produce egg clutches. In addition to straight-crosses, hybrid-crosses were also made